This is the second (continued from

Part 1)

in a series of three blog posts. In the following we'll investigate a few

properties of an object called Conway's topograph.

John Conway conjured up a

way to understand a binary quadratic form – a very important algebraic

object – in a geometric context. This is by no means original work, just

my interpretation of some key points from his

The Sensual (Quadratic) Form

that I'll need for some other posts.

In the following, as mentioned in Part 1,

when referring to a base/superbase, we are referring to the lax equivalent of these notions.

To begin to form the topograph, note each superbase contains only three bases

as subsets. Going the other direction, a base can only possibly be contained as a subset of two superbases:

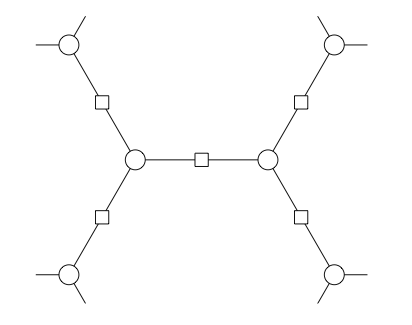

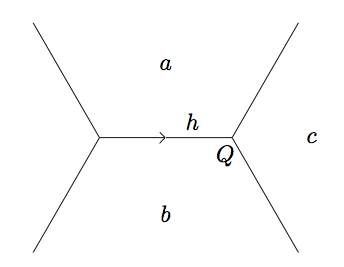

With these two facts in hand, we can begin to form the geometric structure of the topograph. The interactions between bases and superbases (as well as the individual vectors themselves) give us the form. In the graph, we join each superbase to the three bases in it.

Each edge connecting two superbases represents a base and we mark each of these edges with a in the middle. Since each base can only be in two superbases, we have well-defined endpoints for each base (edge). Similarly, since each superbase contains three bases as subsets, each superbase (endpoint) has three bases (edges) coming out of it.

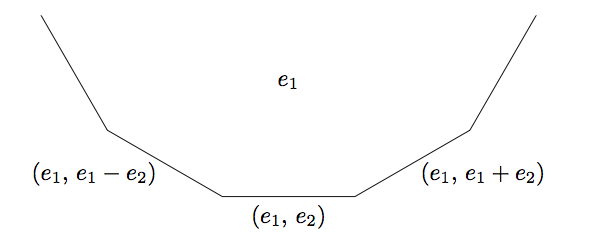

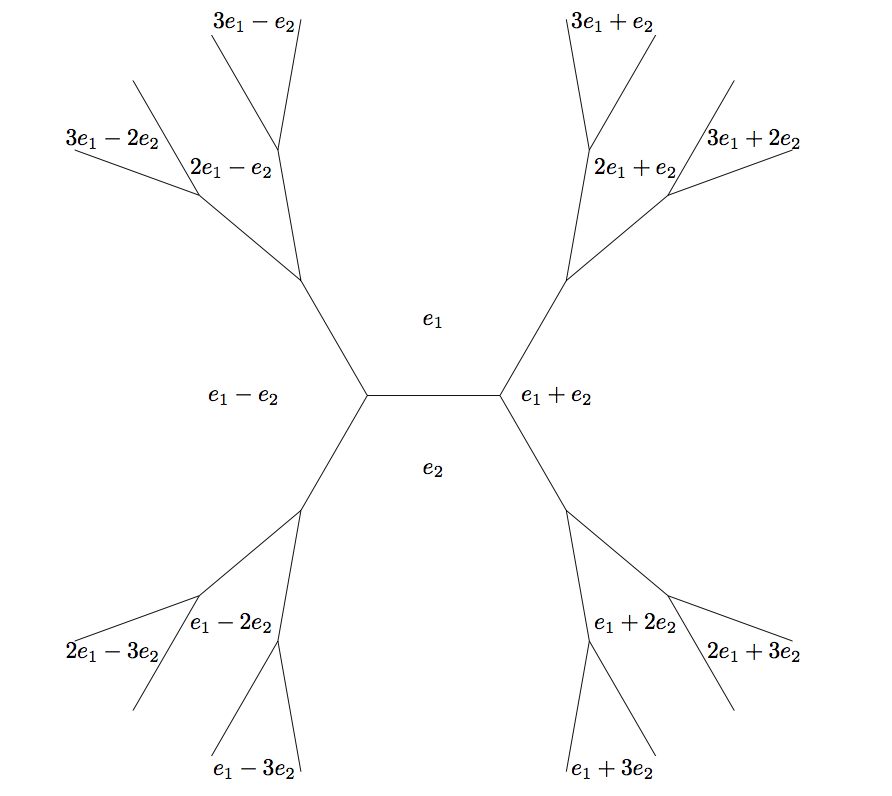

As we traverse each edge (base) surrounding a given vector we move from superbase (vertex) to superbase (vertex), and form a face. Starting from a base traveling along each of the new faces encountered we begin to form the full (labeled) topograph below:

Notice the values of on the combinations of and is immaterial to the above discussion, hence the shape of the topograph doesn't depend on .

If we know the values of at some superbase, it is actually possible to find the values of at vectors (faces) we encounter on the topograph without actually knowing .

Claim:

For vectors

Proof:

Exercise. (If you really can't get it, let me know in the comments.)

This implies that if

then

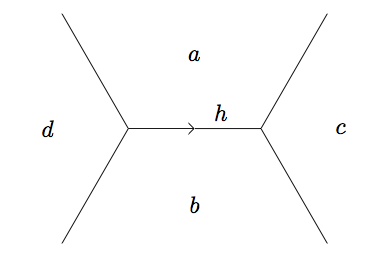

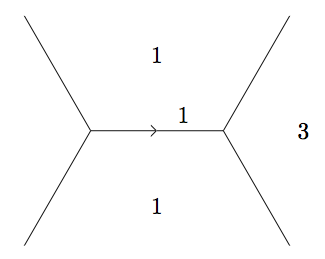

form an arithmetic progression with common difference . This so-called Arithmetic Progression Rule allows us to mark each edge with a direction based on the value of . Hence if we have and the following directed edge:

Obviously starting from a base one wonders if it is possible to move to any pair with and coprime along the topograph. It turns out that we can; the topograph forms a structure called a tree, and all nodes are connected.

Lemma: (Climbing Lemma)

Given a superbase with the surrounding faces taking values and as below, if and the common difference are all positive, then is positive and the other two edges at point away from .

Proof:

First, is positive because hence . The two other edges at have common differences and . Since is greater than both and these differences are positive.

Notice also that this establishes two new triples and that continue to point away from each successive superbase and hence climb the topograph. We can use this lemma (along with a specific form) to show that there are no cycles in the topograph, i.e. the topograph doesn't loop back on itself.

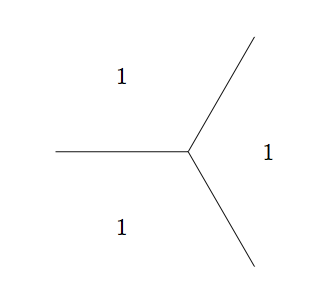

Consider the form which takes the following values at a given superbase:

Due to the symmetry, we may consider traveling along an edge in any direction from this superbase identically. Picking an arbitrary direction, we reach the following superbase:

Since the values must increase indefinitely as laid out by the climbing lemma, the form can't loop back on itself; if it were to, it would need to loop back to a smaller value. Since this holds in all directions from the original well, there are no cycles.

Follow along to Part 3.

Update 1:

This material is intentionally aimed at an intermediate (think college freshman/high school senior) audience. One can go deeper with it, and I'd love to get more technical off the post.

Update 2:

All images were created with the

tikz LaTeX library and can be

compiled with native LaTeX if pgf is installed.